If you have been to the Utah Shakespeare Festival in the last couple of years, you have no doubt seen the work of scenic designer Apollo Mark Weaver. Apollo was gracious enough to answer some questions about his art, being a part of USF, and his inspiration for this season!

About Me

I have always been interested in art and theatre. As a kid, I loved to draw and paint and build things. I was fortunate enough to be exposed to theatre at a young age, so I was always putting on little plays in our living room, conscripting siblings and cousins, and no doubt being a general annoyance to the adults in the room. I also loved creative play, building with Lego toys or making up imaginary worlds. I think I was always creating and always storytelling.

As I got older, I got more involved with theatre, and in college I wanted to be involved in every part of it. I directed shows, I acted, I wrote plays, and I spent a lot of time hanging out in the scene shop building things because I thought it was fun. It really wasn’t until after I graduated that I realized that there was actually a career to be had there, at the intersection of storytelling and art. I spent a lot of my early career as a scenic artist, painting sets and backdrops for various companies and doing design work on the side. A lot of my early design work was for scrappy little storefront theatres or touring children’s theatre, so I learned how to use a certain scarcity of resources as a way to make more interesting creative choices. It’s nice that I don’t have to work that way anymore, but it is definitely a part of my creative DNA as a designer. I’m interested in solutions that are simple but maybe a little weird. That’s often more engaging for me than the obvious choice.

My Process

Everything for me starts with the script and with conversations with the team. We have to have the same understanding of what we want an audience to experience, and good ideas feed each other. I usually do a lot of what I call “emotional research” in the early phases of the process – not so much “What does this look like?” as “What does this feel like?” I often go to artists or movements whose work shares some emotional space with the play. It’s easy to get bogged down in specifics early on, but I find that if you know the emotional truth you’re aiming at, the specifics tend to present themselves.

From there, I tend to go into a combination of 3D modelling and sketching until I find a sculptural space that I think will hold and serve the story. In conversation with the director, I will keep working to modify or reimagine these until we have a look that feels right for the world of the play. We’ll go through an average of about 3 versions before we get to the version that feels right.

From there, my job is to take these concepts and ideas and translate them into things that can actually be created. For a carpentry shop (who build all of the structures out of wood, steel, and other materials), this means creating detailed architectural drafting of everything you see on stage, fully expressing the three-dimensional items in a series of two-dimensional drafting sheets. For a paint shop (who also handle textures, sculpture, and a range of other things), this usually means creating digital or hand-painted images of what the various surfaces should look like. And for a prop shop (who handle furniture, hand props, draperies, and a whole lot of other things), it will be a combination of draftings, research, conversations about stock items, internet shopping, and basically anything you can imagine to figure out how to fill the world of the play.

Once all of that is submitted, we have budget meetings to assess whether what we dream of is achievable with the available resources and how to make adjustments that honor the storytelling while being practically possible. It’s easy to see this process as a series of sacrifices, but I actually think these are the moments that hone and clarify the design. Knowing which elements are worth fighting for and which are not helps me refine and strengthen the design. This is where having a clear eye on the emotional truth pays off. You can determine which elements are serving it and which are just dressing.

For Utah Shakespeare Festival, the above process usually takes about four months, from early September to early January. The shops begin building right after that with a few artisans, and the full summer staff arrives around the beginning of May, which is also when I typically arrive. My time here is spent between rehearsals, shop visits, and creating new information for needs that come up in the rehearsal process. Rehearsals begin in the rehearsal hall, in four-hour blocks, rotating between the shows that share a theatre (three in the Engelstad). Once we get onto the stage, rehearsals move up to 8-hour days that rotate between the shows. Every day, the crew changes the set over so the next show can rehearse with their own set. Gradually, we introduce sound, lighting, and costumes, until we are running the show more or less in real time and then rehearsing portions that need more finessing. This whole tech process is about a month long and requires a lot of stamina from all involved, but we hope the payoff is worth it to our audiences.

Looking Backward

I have spent a lot of time working for Utah Shakes over the years. I have designed 15 shows for the Festival and another 5 shows for SUU in the Engelstad Theatre, so I have come to know this space quite well. It’s not an easy space, and it definitely has a significant learning curve. The challenge for me is always finding how to honor the historically-influenced architecture while also finding ways to make it speak to an audience in new, suprising, and unexpected ways. Last season, we had three very different plays in the Engelstad, which required three very different approaches.

Henry VIII is a play of grandeur and weight. It also has a very explicitly theatrical framing that we wanted to lean into. We used a lot of the existing stage machinery and created an architectural mini-proscenium that was, in part, modeled on Hampton Court Palace, home to Cardinal Wolsey and later of Henry himself. The world had to feel opulent, but full of the weight of consequence as Henry, Margaret, Wolsey, and the rest struggle to build a stable future.

For The Taming of the Shrew, we wanted to lean into the absolute absurdity of the play-within-the-play. The world had to be bigger, louder, and more over-the-top than anything the Engelstad had ever seen. Pulling inspiration from various fantasy worlds from Dr. Seuss to Alice in Wonderland, we created a Padua that was wild, energetic, oversaturated, and absurd.

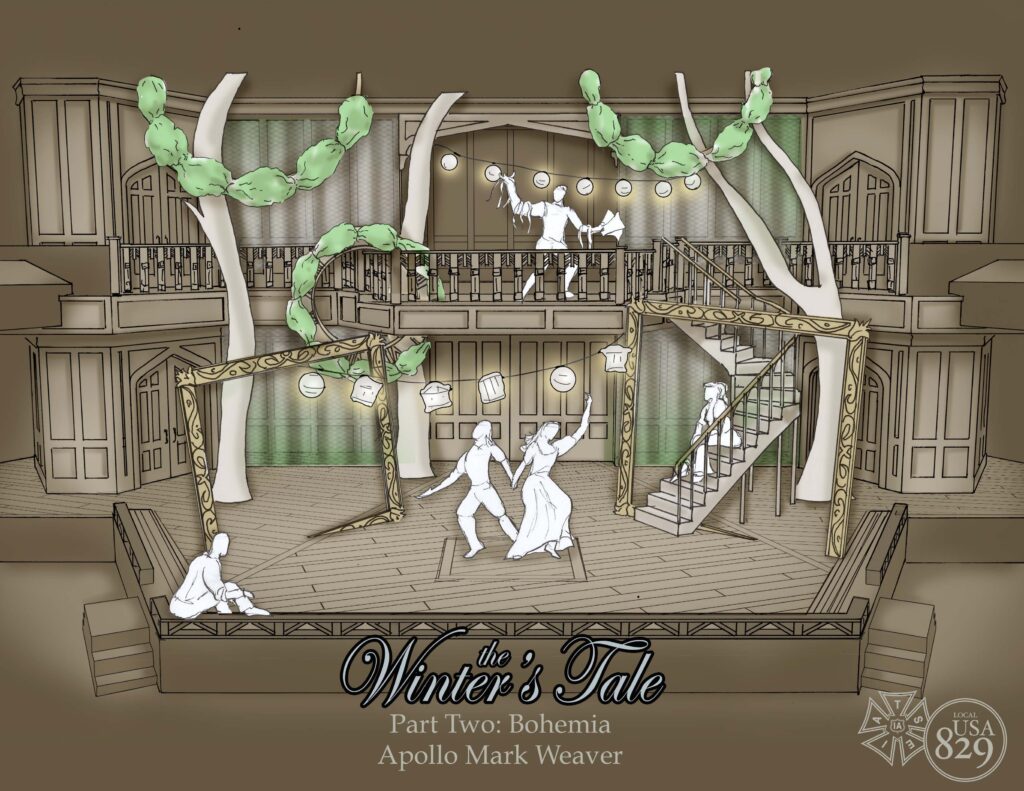

The Winter’s Tale was truly a labor of love. It is one of my favorite Shakespeare plays, and I had never had the chance to work on it before. It felt so important that we get it right. Director Carolyn Howarth (also doing Antony and Cleopatra this year) had such a clear, strong vision for what this beautiful fable wanted to feel like that it was easy to get swept up in it. We were interested in the contrasts – between anger and forgiveness, between art and nature, between joy and terror, and a thousand others. My first sketches included the bear. We envisioned Sicilia as a cold, formal world, just emerging from a barbaric past. The bear is the final breaking of that world, where the horrors of our past come crashing down upon us, but also open the door to a new future. The original idea was that we see that bear rug from the beginning, a symbol of strength and violence, and then it is the rug itself that rises up to kill Antigonus. That idea evolved into the final monstrous bear that audiences saw, which was a combined effort of props, costumes, sound, lights, choreography, directing, and performance. I have seldom had a single moment of staging require so much planning, but it also ranks in my favorite theatrical moments of all time.

You asked the question of how I know when a set has “arrived.” The answer is, honestly, when it opens. Throughout the whole process, I’m seeing new possibilities, things we can expand, reshape, or clarify. There’s always a next thing. Some changes can be made, and some just inform you for the next project, but art is always about refining and assessing. If I could give one piece of advice to aspiring artists, it’s to know that the first try never looks good. There’s a lot of discarded sketches and wrong turns that you have to engage in if you want to find something really satisfying. And even then, there are always things you look at and know you would do it differently if given another chance.

Looking Forward

I don’t want to share too much about this season, for fear of spoiling the magic, but I’ll offer a few thoughts.

I also designed the last production of Macbeth in the Engelstad, and I wanted to challenge myself to think about it in an entirely different way. The guiding idea for me here was that this play sits at the intersection of nature and nightmare.

Antony and Cloepatra is about two massive personalities living out a very personal love story against a background of a world falling into chaos. It is a play of fire and water, passion and violence, and the struggle between the heart and the mind.

As You Like It uses the seasons as a map of our personal growth, our emergence through privation, into freedom, and ultimately into our truest selves.

That’s what I’m going to say about that. Hopefully, when you see the shows, you will feel how these ideas shape the visual world. Ultimately, as a set designer, I provide the first contextual information to an audience as they walk into the theatre. My hope is always that this sets them up for the emotional journey of the story.

Please check out Apollo’s work at his website: apolloweaver.com

I love this peek behind the curtain! Thanks for sharing, I am always awestruct with the stage and the scenery even before the play begins.

Such power there!